Rule of Thumb

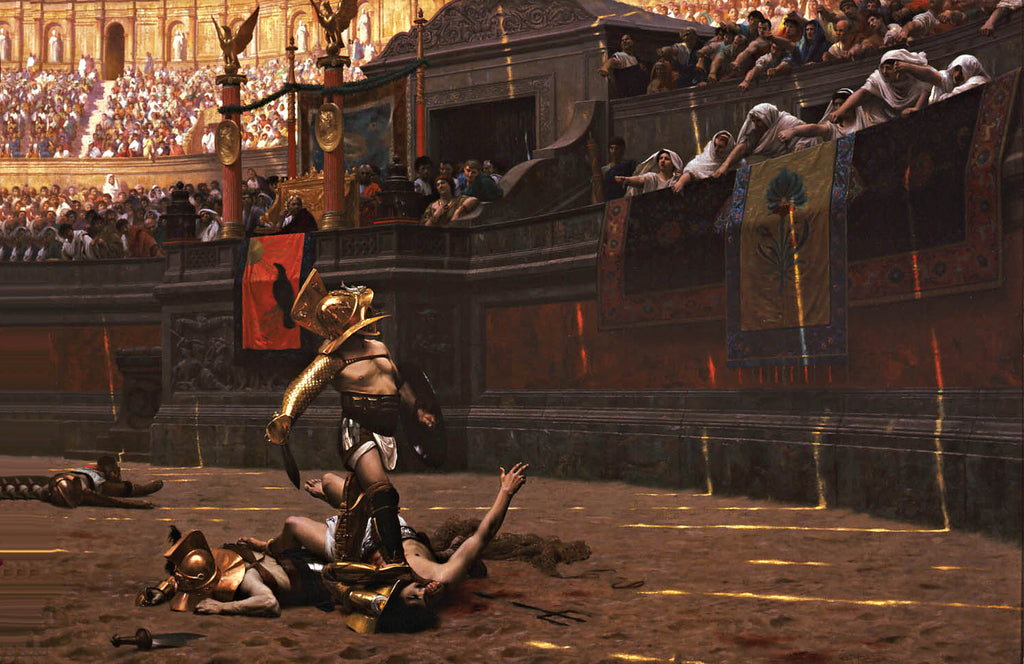

In the Ridley Scott film Gladiator (2000) Maximus, the general turned slave, is advised by veteran fighter Proximo to win the crowd if he wants to win his freedom. And so Maximus proceeds to give all of Rome a show when he steps into the Coliseum, which pays off when his enemy, the emperor Commodus, discovers that he is alive. Though eager to execute Maximus, Commodus is swayed by the crowd and reluctantly gives the thumbs up that allows Maximus to live. It’s a decision that winds up getting Commodus killed—by Maximus, no less—but one whose outcome seems inevitable as soon as the slave-turned-gladiator won the love of the mob.

It’s strange to find our reality contorting to fit our fictions. For today we find ourselves in another arena—social media—where the crowd has commandeered that formerly imperial ability to give a thumbs up or down to whatever, or whoever, grabs its attention. Sure, on social media the stakes aren’t exactly those of life and death, but Twitter, Facebook, and their ilk offer a rapid-fire way to reward winners and punish losers. Just recall the collective delight of the Twitterverse after former Prime Minister Kevin Rudd’s public smackdown of Christian pastor Matt Prater on ABC’s Q&A[1].

Prater had quizzed Rudd on how he reconciled his newfound support for gay marriage with his Christian faith, since Jesus affirmed marriage between a man and a woman. Rudd’s impassioned reply, railing against those who regarded homosexuality as a choice, prompted Tweeters to hail his response the ‘answer of the century in regards to marriage equality’ (by user @Schtang) and ‘an historical moment in Australian politics’ (by @drkerrynphelphs). Rudd had the Twitterati in his pocket that night, whereas Prater was denounced as an anti-gay bigot—a label that, these days, confirms someone’s status as a social pariah. If the Q&A experience made Prater feel ‘a bit like Daniel in the lion’s den’,[2] as he claimed afterward, the abuse he copped on Twitter showed that nothing was shutting the mouths of predators this time round.

Whatever you think of the views or conduct of either Rudd or Prater, the episode suggests that you can emerge triumphant from the sands of the contemporary Coliseum if you’re right on the pulse of the people. But social media is not only today’s Roman arena; it’s a court of public opinion where we crowdsource notions of justice, right, and what are acceptable or unacceptable views. So powerful is the social media set that, in echo of Gladiator’s doomed Commodus, we find figures of authority bending to the whims of the crowd. Rudd’s switch of stance on gay marriage seems a case in point, for it won him a lot of love online. (Though of course Rudd seemed to have had in mind a bigger crowd, one not necessarily well represented on Twitter, when he swooped to the right on refugee policy.)

None of this, of course, grapples with the crucial question of whether it’s wise to leave it to a virtual poll to decide on the ethics of anything. For what if the crowd is wrong?

This problem becomes particularly acute when it comes to unmasking trolls who appear to take a perverse delight in targeting and bullying others online. While people often want trolls exposed for who they really are, public shaming can easily slide into bullying that can have terrible consequences for the trolls in question—even if they, arguably, deserve some form of blowback for their actions. That was certainly the case for Reddit troll ‘Violentacrez’ who, upon revelation of his real identity in October 2012, lost his job and the health insurance that paid for the medical care of his disabled wife.

In an article musing on the ethics (or not) of the outing of ‘Violentacrez’, Danah Boyd, Senior Researcher at Microsoft Research and a Research Assistant Professor in Media, Culture, and Communication at New York University, cuts to the heart of the matter of the crowd acting as moral arbiter: ‘In a networked society, who among us gets to decide where the moral boundaries lie? This isn’t an easy question and it’s at the root of how we, as a society, conceptualise justice.’[3]

The short answer to Boyd’s question is that no one gets to decide. To seek to determine moral boundaries is to assert a vision of the common good and a transcendent standard that applies to us all. But we can’t quite shake the suspicion that such claims are really power grabs in disguise. ‘Whose good, and at whose expense?’ is the inevitable follow-up question. So the more sceptical we are of any overall moral framework, the more we defer to individual choice—a process the Internet is perfect at facilitating.

For as Emily Witt has written, ‘on Google, all words were created equal, as all ways of choosing to live one’s life were equal’.[4] In other words, the rapid return of results of any search query is less concerned with morality and more with enabling choice, since we cannot presume to dictate to others that some choices are better than others.

So if enough people give the thumbs up to anything, it must be OK, because people chose it and choice, as David Bentley Hart reminds us, is ‘the highest good imaginable’[5] of our time. ‘Those of who now… are truest to the wisdom and ethos of our age,’ he writes, ‘place ourselves not at the disposal of God, or the gods, or the Good, but before an abyss, over which presides the empty power of our isolated wills, whose decisions are their own moral index.’[6]

The crowd-sourced verdicts of social media, and even the Internet searches Witt identifies above, are signs of the moral vacuum or abyss Hart describes. In such a context it makes less and less sense to speak of what is right. We spend our time championing our freedom of choice, but neglect to realise that just as important is the ability to choose well. This is why Boyd has no answer to the question she poses, other than by acknowledging that ‘the hard moral conundrums are just beginning’. One thing, however, seems certain. When individual choice reigns, the rule of the mob can’t be far behind.

[1] http://www.abc.net.au/tv/qanda/txt/s3823745.htm accessed 1 Oct, 2013.

[2] http://www.biblesociety.org.au/news/i-felt-a-bit-like-daniel-in-the-lions-den-pastor-matt-prater-challenges-kevin-rudd-on-qa accessed 1 Oct, 2013.

[3] http://www.wired.com/opinion/2012/10/truth-lies-doxxing-internet-vigilanteism/ accessed 1 Oct, 2013.

[4] Emily Witt, ‘What do you desire’. n+1 Vol 16, 2013.

[5] David BentleyHart, Atheist Delusions (Yale University Press, 2009), p22.

[6] Ibid.

Leave a comment

Comments will be approved before showing up.