The Difficulty of Marriage Equality

A Post by Dr John Quinn |

| Photo Courtesy of Free-extras |

|

|

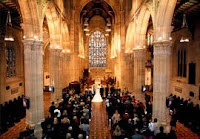

St Andrews Cathedral. Photo courtesy Weddings NSW |

Until the Marriage Act of 1753, there was no statutory requirement to register a marriage relationship and the government had little authority over the process of getting married. That Act introduced a requirement for the marriage to be conducted before a priest of the Church of England, with exceptions for Jews and Quakers. So began the process of government intervention in questions of marriage that continues to this day. With the passage of time the statute has continued to evolve, introducing celebrants and various restrictions over who can and can’t marry. Common law marriage, which the statute effectively replaced, has been slowly disappearing from most jurisdictions.

|

| Photo courtesy Wiki commons |

As Christian people we ought to recognize the authority of government and seek to live quietly in submission to ruling authorities: such is clear from Romans 13:1-7 and 1 Peter 2:13-17. At the same time, the book of Revelation encourages a healthy concern about what over-reaching authorities might do, and the difficulties that might bring upon Christian people. As Christian people we ought to be attentive to the debate about marriage equality, not only because of the Christian view of that institution, but also because of what it says about the government’s perception of its own authority.

Dr John Quinn is Dean of Residents at the New College Village

Leave a comment

Comments will be approved before showing up.

Also in And Just in CASE

Powerful Words: The Key Role of Words in Care

The Powerful Words conference was held at New College on the 26th September. It was planned for chaplains and others interested in pastoral theology and care and was joint initiative of CASE and Anglicare. The conference was based very much on an understanding that Christian chaplaincy is a prayerful cross-cultural ministry that focuses on the needs of others. Chaplains meet people at times of...

The Bible's Story

The Bible has come a long way. In the latest issue of Case Quarterly which is published by CASE we look at the 'journey' that took place to arrive at the Bible as we know it today.

In the beginning was the Word, but it took a while for the hundreds of thousands of words in the Bible to be composed, written down, painstakingly copied, preserved, passed around, tested, accepted, collected together,...

In the beginning was the Word, but it took a while for the hundreds of thousands of words in the Bible to be composed, written down, painstakingly copied, preserved, passed around, tested, accepted, collected together,...