On Holidays with C.S Lewis

English Hospitality

Trevor Cairney

I can remember exactly where I was when I heard the news that John F. Kennedy had been assassinated. I was just eleven years old and JFK was a political giant who seemed to have inspired just about every young boy and girl across the western world. His life and story had touched me in a special way. I had no idea who Clive Staples Lewis was, let alone that he had died on the same day. C.S. Lewis was born on November 29 1898 in Belfast, Northern Ireland, to Albert J. Lewis (1863-1929) and Florence Augusta Hamilton Lewis (1862-1908). Lewis died at 5:30 p.m. at his home ‘The Kilns’ in Oxford on Friday, November 22 1963, one week before his 65th birthday. His death was overshadowed by the momentous assassination of the President. Little more than 30 people attended a small funeral service and burial at his home church, Holy Trinity in Headington Quarry, Oxford, while the world mourned the loss of the President. World leaders from many nations made their way to Washington to farewell John F. Kennedy, and millions watched on television. In the same week a small group of close family and friends farewelled Lewis. The guests included his close friend J.R.R. Tolkien, who was a key player in his conversion.

I was an adult before I discovered the Narnia Chronicles written by Lewis, and it was a further ten years before I became a Christian and understood for the first time the significance of his writing. Later his biblical scholarship was to have a significant impact on me. On the 6th November 2006 I made a pilgrimage to Holy Trinity in Headington to see his church and visit his grave. It was to be a moving time marked by an experience of English hospitality that would have warmed the heart of Lewis. As we wandered around the graveyard a couple in their 80s emerged from the locked church and asked if they could help. We mentioned that we were from Australia and simply came to see the church and the grave of Lewis. “Come in,” they urged, “we’ll make you a cuppa and show you around.” After tea and scones, they did indeed ‘show us around’ and in the process regaled us with tales of their and others’ memories of Lewis and his brother. They showed us the favoured pew where Lewis and his brother Warren Hamilton (‘Warnie’) Lewis sat each week, with Clive always preferring to sit as close as possible to one of the central pillars. They showed us the Narnia window, and spoke of Lewis’s involvement in the church. They then led us out to his simple grave, we chatted some more, we wished each other God’s richest blessings and parted, no doubt not to see each other again until that blessed day when they, we and Lewis himself will be gathered around the throne of God worshipping him eternally (Revelation 7:9-17).

Lewis on the Bible, the Bible on Lewis

Greg Clarke

C.S. Lewis is sometimes hauled over the coals for his allegedly low view of Scripture. I have always found this criticism of him confusing. Lewis never presents a "theology of the Bible" or a "guiding sacred hermeneutic", and for that I am truly grateful. What Lewis does consistently is approach Scripture on its own terms: certainly, as forms of literature, interconnected and grounded in culture; but even more importantly as the transforming Word of the Spirit of God. Ironically, it is Lewis's respect for the nature of Scripture that draws criticism from some Christian readers.

Lewis was highly skeptical of modern biblical scholarship, with its atomizing and demythologizing instincts. Instead, he urged readers to notice and study the literary forms of Scripture, allowing such devices as imagery, rhetoric, myth and genre to light the path to the truth. For Lewis, these are the creative means by which God communicates with his creatures.

Lewis clearly does approach the Bible through the lens of historical church ("The basis of our Faith is not the Bible taken by itself but the agreed affirmation of all Christendom, to wh[om] we owe the Bible itself")[1] and perhaps would count as a Barthian ("It is Christ himself, not the Bible, who is the true word of God. The Bible, read in the right spirit and with the guidance of good teachers will bring us to Him”)[2]. But the labels are largely unhelpful. In contrast, reading his works of literary criticism, apologetics, cultural analysis and ‘amateur’ theology, one is struck by his deep personal devotion to the morally convicting character of Scripture, his compendious knowledge of the history of its interpretation, and his subtle sensitivity to the implications of biblical stories and teachings.

In a lovely blend of Platonic philosophy and Christian humility, Lewis’s final position on Scripture can be expressed in a simile: it is like a mirror, in which we are to gaze in order to truly see ourselves and the world, not dictating what we see, but seeing what God has revealed:

“Originality” in the New Testament is quite plainly the prerogative of God alone; even within the triune being of God it seems to be confined to the Father. The duty and happiness of every other being is placed in being derivative, in reflecting like a mirror.[3]

[1] Walter Hooper (ed), The Collected Letters of C.S.Lewis Vol III, HarperCollins, New York, 2007, p.653.

[2] Hooper, Letters III, p.246.

[3] C.S.Lewis, “Christianity and Literature” (1939) in Christian Reflections (ed. Walter Hooper), Geoffrey Bles, London, 1967, p.6.

Sharpen Your Conversations in Lewis' Toolshed

Chris Swann

You get talking with a friend about their objections to Christian faith. The conversation starts to gather momentum. You seem to be getting more and more opportunity to speak personally about Jesus and about the reasons for your trust in him.

But suddenly there’s a metaphorical screeching of the wheels. You feel a sickening jolt.

Perhaps you’ve struck a fissure in the conversational rails, colliding with some unforeseen personal investments around an issue like same-sex marriage.

Or perhaps you’ve rounded a corner too quickly, barrelling at speed into some aspect of apologetics that you expected to bluff your way through using second-hand facts and figures (about the fine tuning constants in the universe or whatever).

Or perhaps you were too well-prepared, and allowed your ability to speak at length and in detail on your personal field of expertise to hijack your desire to talk about Jesus.

Whichever way it happened, your once pleasant and apparently promising conversation has been derailed—and may even be careening out of control towards some ominously looming interpersonal cliffs…

If you’ve ever found yourself in this situation then maybe, like me, you have something to learn from C.S. Lewis’s famous ‘Meditation in a Toolshed’._

Lewis introduces his meditation by recounting his experience of standing in a darkened toolshed. A single sunbeam, originating from a crack at the top of the door, cuts across the shed.

After describing the difference between his experience of looking at the sunbeam and looking along it to see the scene outside, he generalises this to two approaches to knowledge: the ‘external account’ of something, and knowing about something ‘from inside’.

For Lewis, this important distinction was itself an apologetic tool. It helped him challenge the hubris of the ‘scientific’, modernist approach to knowledge—especially its inveterate insistence on the absolute superiority of the ‘external account’.

But for me, it’s more significant as a way to sharpen my sense of how to answer questions.

To begin with, it helps me ask myself questions about how well my responses ‘look along’ my faith towards the One who is its object. A classic biblical passage about this is 1 Peter 3:15:

But in your hearts revere Christ as Lord. Always be prepared to give an answer to everyone who asks you to give the reason for the hope that you have. But do this with gentleness and respect…

In these terms, does my response move out of my reverence for Jesus? Or is it shaped by other forces—like my desire to win the argument or gain approval?

Likewise, I’m learning that it’s one thing to launch a battery of apologetic arguments or draw on conversational tactics that I’ve carefully gathered and memorized, but it’s something quite different to give the reason for my hope in Christ. For, ultimately, giving the reason for my hope is something that, if I were to do it, might possibly help my conversation partner look along my testimony to see Jesus, rather than simply looking at it to see how intelligent (or well-rehearsed) I am.

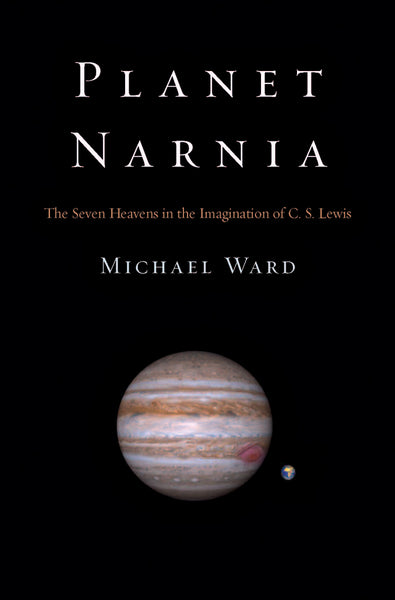

On Planet Narnia

David Scarratt

Planet Narnia by Michael Ward is an answer to the ‘problem of composition’ of the Narnia Chronicles: whether the series has a unifying principle, and whether the elements that strike many readers as out of place (such as Father Christmas in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, or Bacchus in Prince Caspian) can be fitted coherently into a non-arbitrary structure. Two features of the composition of the Chronicles are patent: they have something to do with presenting Christianity in a positive light, and they are stories for children. Ward offers detailed evidence that there is an organising principle that makes sense of these other features and influences the distinctive form of each book according to its place in an overarching scheme.

The scheme that Ward believes unifies the Narnia Chronicles is derived from an area of Lewis’s own expertise, the literature of the Middle Ages. A particular conception of the structure of the cosmos runs through much of this literature, and Lewis explored this cosmic model in some of his lectures and academic works, The Discarded Image being an important instance. The planets are key to this scheme—the planets as understood in the Middle Ages, that is: the Moon, Mercury, Venus, the Sun, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. Seven ‘planets’, to go with seven Chronicles of Narnia. Ward’s contention is that each book reveals the influence of the planetary spirit under which it was born.

Thus, The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe manifests the spirit of the literary Jove: a wise and benevolent ruler bringing peace to his domain. Prince Caspian is imbued with a Martial ethos, both the tragedy and the honour of war, but mingled with an older sylvan association of Mars. The Voyage of the Dawn Treader is Sun-struck and golden, The Silver Chair Moon-lit and pale. Mercury and Venus in their various guises govern The Horse and His Boy and The Magician’s Nephew, respectively, and The Last Battle has Saturnine qualities. Ward combs Lewis’s academic, poetic and popular writing for his views on the nature and connotations of each planet, then presents many instances of these elements emerging in details in the corresponding story. In each case, Ward claims that Aslan is presented in a way that reinforces the atmosphere and spirit of the story: Aslan is the all-in-all of this planetary, or rather cosmological, system.

Ward makes the case that each book reflects characteristics of its governing planet persuasively. There is a mass of detail, well-presented with comprehensive background material. Where more work could be done is in demonstrating that these characteristics are largely confined to the respective book, and are not instead all jumbled together throughout the series. The elements Ward presents in support of his claims are sometimes not exclusive to one book, and the relative numbers often seem too small to discriminate. But while there are dissenters, many have found the case convincing. For me, the interest this cosmological model held for Lewis, and the attitude he expresses towards it in works like The Discarded Image and some of his scholarly essays, make the general thesis very plausible.[1]

For its clear presentation of ideas that obviously appealed to Lewis, and its insightful analysis not just of the Narnia Chronicles, but incidentally of other works by Lewis, including some lesser-known pieces, the book is a richly rewarding read.

[1] A documentary called The Narnia Code presents a less rigorous, and more easily consumable version of Ward’s argument, and a book based on the documentary has been published under the same title.

'My Friend of Friends'

Bradley M Wells

Like many self-confessed Anglophiles, I can’t resist a pilgrimage to the ‘Eagle and Child’ in Oxford whenever I am back in the Mother Country. This small but sacred pub, symbolically located on St Giles Road opposite the Martyrs’ Memorial and just down from Pusey House, stands as a shrine to that famous group of Oxford writers, The Inklings. On the wall in one of the drinking booths is a collection of photographs of the key members of the group. Most prominent, right in the centre, are the pictures of C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien; the two men who would go on to be giants of twentieth century literature, and perhaps more importantly for the publican, the establishment’s biggest tourist drawcard.

Whether or not you sit down in that booth and have an empathic pint of cider, it is hard not to feel the inner glow of this place. The Inklings have taken on mythical status and are rightly remembered as a paradigm of ideal companionship, or what Lewis calls the laudable and rare phenomenon of ‘Clubbableness’.[1] But was it also a paradigm of what Lewis identifies as ‘divine Friendship’—that ‘happiest and most fully human of all loves; the crown of life and the school of virtue?’[2]

To find an answer to this question you need to cast your eye just a little further out from the centre of these photographs and toward the less familiar figures. Here you will see a photograph of a slightly quirky looking figure who holds the key—Charles Williams.

Rather than Tolkien, or any other Inkling for that matter, it was Lewis’s relationship with Charles Williams that came closest to being a genuine experience of the true love that is divine Friendship. The uniqueness of their relationship is fittingly acknowledged in Lewis’s seminal work on friendship, The Four Loves. In his only explicit reference to a personal friend in this book, he cites his affection for Williams as an example of the divine joy when both friends ‘see the same truth’.[3] It was in Williams that Lewis found his experience of true Friendship, of the type that ‘exhibits a glorious “nearness by resemblance” to Heaven itself’.[4] Here was ‘a relation between men at their highest level of individuality’.[5] Even their first contact was prophetic. Guided by divine providence perhaps, they spontaneously felt compelled to initiate first contact at the same time, unbeknown to each other, when Lewis wrote to Williams to congratulate him on his novel, The Place of the Lion, just when Williams was writing to Lewis in response to his reading of The Allegory of Love. One likes to imagine the letters passing each other that day in May 1936 through the Royal Mail as an act of what Williams would call ‘Exchange’. Whether the inspiration was earthly, divine or more likely both (what Williams would call ‘co-inhered’), the synchronicity between the two men was immediate and intense, whereby, in Lewis’s words, their ‘friendship rapidly grew inwardly to the bone’.[6]

Williams was immediately invited to attend The Inklings while still living in his beloved London, but it was with his ‘forced exile’ to Oxford at the start of the War in 1939 that the two men’s lives became truly entwined. Lewis quickly became Williams’s greatest advocate among the Academe, declaring of his lectures on Milton’s Comus: ‘as criticism it was superb... [the Divinity School] had probably not witnessed anything so important since some of the great medieval or Reformation lectures’.[7] Williams’s literary, theological and critical reputation continued to grow at Oxford and he was awarded an honorary MA in 1943, again partly due to the lobbying efforts of Lewis.

Williams’s impact upon The Inklings while at Oxford was equally immediate and profound. Indeed, as Lewis explains, he soon became the key figure in the group:

The importance of [Williams’s] presence was indeed, chiefly made clear by the gap which was left on the rare occasions when he did not turn up. It then became clear that some principle of liveliness and cohesion had been withdrawn from the whole party: lacking him, we did not completely possess one another.[8]

Williams’s friendship also had a significant impact upon Lewis’s own writings. That Hideous Strength, being Lewis’s third book in his Science Fiction Trilogy, is clearly influenced by Williams’s style, including the Arthurian subject matter and even the language, which is directly taken from Williams’s own Taliessin mythology. Even Lewis’s short story ‘The Shoddy Lands’[9] is based on Williams’s depiction of the afterlife in All Hallows Eve (1945).[10]

The depth of their professional and personal friendship can be seen most clearly in the impact that Williams’s premature death in 1945 had upon Lewis. Not only would The Inklings ‘never be the same again’,[11] Lewis was personally devastated by this ‘greatest’ loss of his ‘masculine angel, spirit burning with intelligence and charity’.[12] However, William’s death also had a profound spiritual effect on Lewis, who declared, ‘no event had so corroborated my faith in the next world as Williams did simply by dying’.[13]

The spirit of Williams would indeed stay with Lewis the rest of his life. Like a timeless co-inhered character from one of Williams’s novels, his ‘divine Friend’ would stay with him and be invoked whenever needed. One of Lewis’s students noted much later how Lewis ‘had a near-fanatical devotion to Charles Williams’,[14] and he continued to cite Williams when trying to explain difficult literary or theological concepts, such as when explaining to a correspondent the true power of prayer:

The really efficacious intercession is Christ’s, and yours is in His, as you are in Him, since you became part of His ‘body’, the Church. Read Charles Williams on Co-inherence in almost any of his later books or plays (Descent of the Dove, Descent into Hell, The House of the Octopus).[15]

So, in the year when we remember Lewis’s death, we would be wise to also consider an earlier one. With the death of Charles Williams, Lewis’s ‘friend of friends, the comforter of all our little set [The Inklings], the most angelic man’[16] entered the divine City, only to be re-united with his true friend some eighteen temporal years later. And while the full significance of this unique friendship is yet to be acknowledged, its fruits are unmistakable in the impact each had upon the other’s writings and the broader development of theology and literature in the twentieth century.

Perhaps it is time we moved that photograph of the quirky-looking fellow on the wall in the ‘Eagle and Child’ just a little bit closer so that these long-departed friends can be re-united in image here and now, as they co-inhere in eternal reality.

Bradley M Wells

Bradley is currently completing his PhD in English Literature at The University of Sydney where he is Vice Master of Wesley College. He is a founding member of ‘The Sydney Inklings’.

[1] C. S. Lewis, The Four Loves (Bles, 1960), p77.

[2] Ibid., p69.

[3] Ibid., p83.

[4] Ibid., p74.

[5] Ibid., p72.

[6] C.S. Lewis (ed.), Essays Presented to Charles Williams (Oxford University Press, 1947), Preface pviii.

[7] C. S. Lewis, The Collected Letters ed. Walter Hooper (Harper Collins, 2004), Vol 2, pp345f. These lectures by Williams prompted Lewis to re-read Milton’s Paradise Lost and present his subsequent Ballard Matthews Lectures at University College, North Wales in 1941, which was enlarged to form his Preface to Paradise Lost published in 1942 and dedicated to Williams.

[8] Essays Presented to Charles Williams, Preface pxi.

[9] Published in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction 1956.

[10] See Bruce Edwards, C. S. Lewis: Life, Works and Legacy (Praeger, 2007), p158.

[11] Humphrey Carpenter, The Inklings (Allen and Unwin, 1978), p200. Citing Warnie Lewis’s diary entry on the day of Williams’s death, 15 May 1945.

[12] Essays Presented to Charles Williams, Preface pix.

[13] Ibid., pxiv.

[14] H. M. Blamires, undated post-1963 letter quoted in Warren H Lewis (ed.) Letters of C.S. Lewis (New York: Brace & World, 1966), pp18f.

[15] Lewis, The Collected Letters. Letter to Rhoda Bodle, Oct 24th 1949.

[16] Letter by C.S. Lewis cited in Douglas Gilbert and Clyde Kilby, C.S. Lewis: Images of His World (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1973), p48.

On the Pleasures of Reading

Rosemary Albert

No book is really worth reading at the age of ten which is not equally (and often far more) worth reading at the age of fifty –except of course, books of information. The only imaginative works we ought to grow out of are those which it would probably have been better not to have read at all.[1]

Few of the Wise Sayings of C. S. Lewis have given me as much ruminative pleasure as this one, from his essay On Stories.[2] What does he mean?

If we look for a tidy definition of ‘worth’ we will look in vain. Lewis begins his essay, On Stories, by describing his reading experiences in terms of the ‘pleasure’ they have given, and this not equally available from all books, and not available to all readers. (To his surprise he discovered that many readers did not enjoy stories in the same way he did; their enjoyment was of a different kind to his.) We’re not usually encouraged to take pleasure seriously, but Lewis seems to have no trouble doing so. For him the pleasure depended on the quality of the imaginative experience. Rider Haggard’s King Solomon’s Mines ‘lays a hushing spell on the imagination’[3] another story merely provides excitement. What it ‘does to us’ separates one book from another. The quality of his imaginative response to Jack the Giant Killer depends on ‘the hero surmounting danger from giants’.[4] Such stories give increasing pleasure when reread, because the suspense is out of the way, and the reader is free to enjoy the ‘poetry’,[5] the quality of imaginative experience that is its enduring worth.

And imaginative literature can take us to places where realistic story or theorems can never go. If we have read The Hobbit, if we know Dorothy Sayer’s The Man Who Would be King[6], or the story of Oedipus, we will be familiar with stories of prophecy and fulfilment, where sometimes the very efforts to thwart the prophecy bring about its fulfilment says Lewis. We have ‘seen ... what has always baffled the intellect.’ The effect on him is both ‘awe’ and ‘bewilderment’. ’It may not be like ‘real life’ in the superficial sense, but it sets before us an image of what reality may well be like at some more central region.’[7]

So to explain what is ‘worth reading’ he gives us accounts of experience, not abstractions. A book that is worth reading is a book that gives us access to the deeper imagination. The kind of reading that is happening is the indication that it is worthwhile. Allow it to have its effect on us, he says. He takes up this idea in An Experiment in Criticism[8], more explicitly directing us to the elements of the work itself, to form and idea: to the words, to the rhythm, to the evocative nature of good writing, to design, pattern and content before settling for a definition: A good book is one which invites and permits good reading. If it invites, we can take a closer look to see what makes it work; it is worthy of further inquiry into its literary qualities. It should at least entertain, give pleasure; this is the entry test.

The enjoyment of literature needs no justification, Lewis argues. Yet its great value for him is this: it enables us to ‘see with other eyes’;[9] ‘it admits us to experiences not our own’.[10]

I had neglected imaginative literature for decades for more ‘important’ things. When I read Robert Fagle’s translation of The Odyssey[11] for the first time soon after turning fifty, and travelled Homer’s ‘wine dark sea’ (how strangely evocative are those words), when I saw with other eyes the ancient world, somehow akin to the ancient world of the Bible yet new to me, I realised that my world would never be quite the same. I had travelled somewhere and returned, changed.

I enjoy reading and I want to share this pleasure with those I love, and so choosing books for our children and grandchildren keeps me busy. I intend to give experiences, when I choose books, but it is always an experiment. Tastes vary. They won’t all pass Lewis’ final exam, but I do hope there will be pleasure wrapped within each book.

[1] C. S. Lewis, On Stories, In Of This and Other Worlds Ed. Walter Hooper (London: HarperCollins 1982) p.27.

[2] On Stories, pp.15-33.

[3]Ibid p.18

[4] Ibid p.20 The emphasis is his

[5] Ibid p. 30

[6] Her play cycle on the life of Christ

[7] On Stories pp.27-28 The emphasis is his

[8] C. S. Lewis, An Experiment in Criticism (Cambridge:Cambridge University Press 1961)

[9] Experiment p.137

[10] Ibid p.139

[11] Homer, The odyssey Tr. Robert Fagles (New York:Penguin Books 1997)

Leave a comment

Comments will be approved before showing up.